Hi! So I work as an intern for the Whipple observatory helping run several science instruments here. The nights can get kind of slow sometimes due to crappy whether. When that happens, sometimes I end up blogging about it.

Since I've been working for the Whipple observatory, once a month, I work at these small observatory's. These observatories are about as old school as you can get, being built around the 1960's.

The view outside the buildings is fantastic! Here is a picture I took close to the observatory, facing towards Mexico about an hour before sunset.

The telescope I use is called the Tillinghast telescope. Most here call it the 60 inch or the 1.5 meter.

Because stars are so astronomically far away from Earth, unless you have a telescope with a size out of this world, you can't resolve them. However, I do spectroscopy using the FAST instrument, which is a nitrogen cooled spectrograph that doesn't need a huge mirror or the star to be resolved.

Just to give a really quick and simple explanation of what the FAST spectrograph does, any spectrograph splits light up by its color kind like a prism does. Even if you can't resolve a star, you can learn a lot about a star by looking at what types of colors it has and how much those different colors the star is producing (or not producing). Some of the things you can learn are things like what elements are in the star, what temperature the star is, how fast it's spinning, if it has really strong gravity, etc. Because FAST is cooled with liquid nitrogen, it can take super precise spectrographic measurements of any stars it sees, allowing it to measure really dim stars.

So beyond the super interesting astronomy science that is done with FAST, one of the most fun parts of my job is actually when I figure out which stars are best to measure and then 'drive' the telescope and locate those stars. When I choose a star, not only does it have to be an interesting star, it also has to be within the range of the telescope (as it's hard to look at stars through the earth)! A neat way you can visualize how stars move across the sky is using

https://stellarium-web.org

Now pretend I have chosen to look at the star Capella, which you can search for using stellarium. If you change the time on that website, you can see that Capella will move across the sky. Part of my job is to figure out what time is best to look at Capella to get the best data.

Once I've chosen the best time to measure Capella, I then enter Capella's coordinates into the telescope software and the telescope then slews (or points) to the entered coordinates at my chosen time. Once the telescope gets there I see two things pop up on some computer screens. The first is a star chart and the second is the telescopes 'guy cam'. Since the telescope isn't able to perfectly point to the correct place, the guy cam shows me exactly where the telescope is pointing. Using the included star chart I manually move the telescope until it's lined up correctly.

If everything goes as planned, using the guy cam, star charts, and my target list, I do this all night taking measurements of various stars. Things rarely go perfectly though, with one of the most common things to go wrong being clouds rolling in, almost literally at times.

Clouds spell trouble for astronomy and it's very important to make sure that the observatory isn't open if it's possible the telescope might get wet. I close the observatory if there is any chance of rain, if the dew point gets too close to the outside temperature, or if the humidity gets too high. This is because the telescope mirror is a large piece of reflective metal with nothing to protect it. Getting a bunch of metal wet generally leads to the metal corroding. A corroded mirror is just a straight up bummer as corrosion isn't reflective at all and being reflective is pretty much a mirror's job.

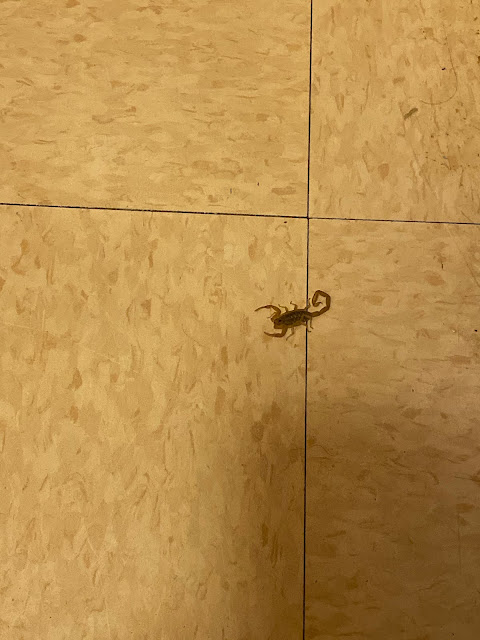

I then wait to see if the weather clears up. If it clears up, I start taking data again. If not, sometimes I write blogs about astronomy, eat food, write emails, write applications, listen to music, and hope that the weather will get better. Sometimes I even come across scorpions in the observatory!

At the end of the night I go through a detailed checklist and make sure that things are put away correctly, all the important switches have been switched appropriately, that the telescope is properly stored so as to not be exposed to the elements, and that the nitrogen tank on the FAST instrument is properly filled so FAST is properly cooled until the next day.

Thanks for reading and I hope you enjoyed me sharing! If you are curious about other things in astronomy, let me know and maybe I'll blog about it at some point. Be sure to follow me (and of course share it if you feel so inclined). If you want to know more about life up here on the mountain, check out this other blog I wrote

https://astronomaestro.blogspot.com/2019/11/what-life-is-like-as-observational.html

Also don't get stung by a scorpion, as it would really suck if that happened.

Have a stellar day ;)!

Since I've been working for the Whipple observatory, once a month, I work at these small observatory's. These observatories are about as old school as you can get, being built around the 1960's.

The view outside the buildings is fantastic! Here is a picture I took close to the observatory, facing towards Mexico about an hour before sunset.

The telescope I use is called the Tillinghast telescope. Most here call it the 60 inch or the 1.5 meter.

Because stars are so astronomically far away from Earth, unless you have a telescope with a size out of this world, you can't resolve them. However, I do spectroscopy using the FAST instrument, which is a nitrogen cooled spectrograph that doesn't need a huge mirror or the star to be resolved.

Just to give a really quick and simple explanation of what the FAST spectrograph does, any spectrograph splits light up by its color kind like a prism does. Even if you can't resolve a star, you can learn a lot about a star by looking at what types of colors it has and how much those different colors the star is producing (or not producing). Some of the things you can learn are things like what elements are in the star, what temperature the star is, how fast it's spinning, if it has really strong gravity, etc. Because FAST is cooled with liquid nitrogen, it can take super precise spectrographic measurements of any stars it sees, allowing it to measure really dim stars.

So beyond the super interesting astronomy science that is done with FAST, one of the most fun parts of my job is actually when I figure out which stars are best to measure and then 'drive' the telescope and locate those stars. When I choose a star, not only does it have to be an interesting star, it also has to be within the range of the telescope (as it's hard to look at stars through the earth)! A neat way you can visualize how stars move across the sky is using

https://stellarium-web.org

Now pretend I have chosen to look at the star Capella, which you can search for using stellarium. If you change the time on that website, you can see that Capella will move across the sky. Part of my job is to figure out what time is best to look at Capella to get the best data.

Once I've chosen the best time to measure Capella, I then enter Capella's coordinates into the telescope software and the telescope then slews (or points) to the entered coordinates at my chosen time. Once the telescope gets there I see two things pop up on some computer screens. The first is a star chart and the second is the telescopes 'guy cam'. Since the telescope isn't able to perfectly point to the correct place, the guy cam shows me exactly where the telescope is pointing. Using the included star chart I manually move the telescope until it's lined up correctly.

If everything goes as planned, using the guy cam, star charts, and my target list, I do this all night taking measurements of various stars. Things rarely go perfectly though, with one of the most common things to go wrong being clouds rolling in, almost literally at times.

Clouds spell trouble for astronomy and it's very important to make sure that the observatory isn't open if it's possible the telescope might get wet. I close the observatory if there is any chance of rain, if the dew point gets too close to the outside temperature, or if the humidity gets too high. This is because the telescope mirror is a large piece of reflective metal with nothing to protect it. Getting a bunch of metal wet generally leads to the metal corroding. A corroded mirror is just a straight up bummer as corrosion isn't reflective at all and being reflective is pretty much a mirror's job.

I then wait to see if the weather clears up. If it clears up, I start taking data again. If not, sometimes I write blogs about astronomy, eat food, write emails, write applications, listen to music, and hope that the weather will get better. Sometimes I even come across scorpions in the observatory!

At the end of the night I go through a detailed checklist and make sure that things are put away correctly, all the important switches have been switched appropriately, that the telescope is properly stored so as to not be exposed to the elements, and that the nitrogen tank on the FAST instrument is properly filled so FAST is properly cooled until the next day.

Thanks for reading and I hope you enjoyed me sharing! If you are curious about other things in astronomy, let me know and maybe I'll blog about it at some point. Be sure to follow me (and of course share it if you feel so inclined). If you want to know more about life up here on the mountain, check out this other blog I wrote

https://astronomaestro.blogspot.com/2019/11/what-life-is-like-as-observational.html

Also don't get stung by a scorpion, as it would really suck if that happened.

Have a stellar day ;)!

Comments

Post a Comment